Ancestral Longing

Thin Places & the House of Memory

Dear Fellow Dreamer,

When I was a kid, my gramma told me that on top of being a farmer, her dad had been a barn fiddler at the square dances where she’d twirled, in the Eastern Townships of Québec. Throughout my tween and teen years, it was a detail that connected me with him, since for about a decade, I was a violin player, too. The instrument was one I’d simply taken to, and even though I mostly played classical music in school and community orchestras, I loved the sound of old-time fiddling. In my mind, I conjured Gram’s girlhood quadrilles—the kinetic jig steppers, and the music makers’ wild bow strokes and foot stampings and leanings. I wondered about my great-grandfather. What was his music like? When I was fifteen, at Gram’s urging, my father finally descended the steps of her shadowy old crypt of a Victorian cellar in Stratford, Ontario, sixty years and 450 miles from those country reels. He was to locate and bring up his grampa Ernie’s fiddle—one Dad remembered the old man playing in the streets the day the war ended in 1945. Could that violin become mine? Could I play it, too? Yet in its musty cracked case, the wooden belly, ribs, and back plate lay in pieces.

How many of us think about old family stories and our ancestors at Hallowe’en? In this stretch from Samhain’s approach right through to the Solstice, do your thoughts turn to the past? To another world? One an eyelash’s width away from this one, perhaps, yet also—somehow—right here?

Journeys

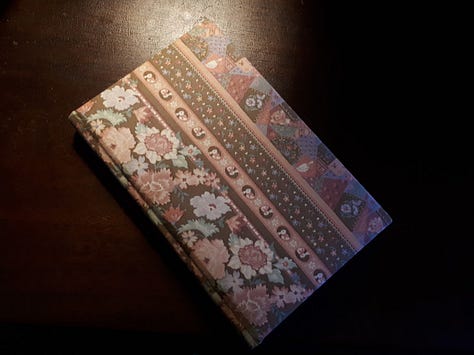

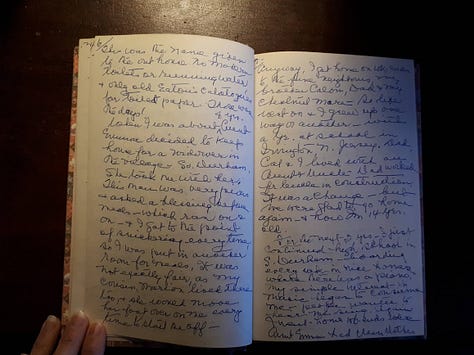

Except in my imagination, I never went to the Eastern Townships as a child, or even as a young adult. It wasn’t until 2021, a year after my father’s death, that my husband and I first made the trip a few hours east of where we now live. In 2025, for my 60th birthday, I wanted to revisit those farm fields, a country cemetery, and a particular stretch of unpaved road. I wanted to get to know my great-grandfather Ernie better, and to find out for sure this time if the house he built for himself and his two children still stands. So, earlier this month, we returned. And not without my big canvas tote stuffed full of treasures: thick family tree files, old photographs, and my gramma’s journal that, in 1986, had begun as a blank notebook I’d given her for her 82nd birthday. A book she filled with stories.

Gram’s family stories—her wistful, often lively, comical accounts of growing up on her father’s farm—have brought joy, occasionally answers, and always comfort in my life, even though some of those stories are sad.

After the recent death of film icon, Robert Redford, I was taken with a replay of an interview he’d given, in which he spoke of sadness as fundamental to our experience:

“I think life is essentially sad. It has great moments of happiness… great moments of joy… but sadness is like a current running through it. It’s just there. It pops up. It’s something I believe in drawing on because I think it’s real.”

In seeking to learn more about my great-grandfather Ernie on our latest trip, as usual, it was impossible to overlook an underlying current of sadness that shaped their lives. And mine.

Since girlhood, I’ve been compelled by the story—or more precisely, the gaps in the story—of Ernie’s wife, my great-grandmother Jessie, who, like her husband, came from a big family that had farmed for several generations in the Townships. Unlike her husband, as a very young woman, Jessie moved to Ithaca, New York, to work in the fine home of a Cornell theology professor and his wife: a farm girl’s equivalent to finishing school. The couple treated her as their daughter. In my grandmother’s words, Jessie became “quite a lady.” In her journal, Gram adds, “They did not wish her to return to her parents and marry my father—but such is life and love.”

Last year at this time, I shared several poems about Jessie in a post called “The Haunts We Seek.” There, I touch upon what happened to her—how, when my grandmother was six and her brother three, Jessie developed a tumour that led to her having a hysterectomy, and later, severe unshakeable depression. In a time when western doctors understood so little about women’s health, including the impacts of a hysterectomy on the endocrine system, and about mental illness generally—when surgeons didn’t leave ovaries and no hormone replacement therapy existed—this accomplished 37-year-old woman went to Montréal, ostensibly for a brief stay, and disappeared behind institutional walls for fifty years.

My cousin and I often wonder about the treatment of our great-grandmother during those early and middle decades of the 20th century, when mentally ill women were warehoused, their conditions managed by medical professionals. Their stories, too. Even the most sanitized and clinical accounts of my great-grandmother’s life would be a gift. But at the hospital, her records were destroyed.

A few weeks ago, I found myself thinking about Jessie and Ernie’s long-distance courtship—how strong their attraction must have been to bring them back to each other after Jessie’s early years away in Ithaca. I thought of their wedding in a little white church on Christmas Eve, 1899. Of the horses and sleighs and bells. The sound of the fiddles and dancing.

And I found myself feeling as I had on my previous trip. Falling in love with the land itself.

Thin Places

One of the books I’ve been reading this month is Frank MacEowen’s The Mist-Filled Path. He describes “threshold places”—areas in the landscape where we feel our otherworldly senses stirring. An innate inner tuning to something just beyond ordinary reality—something close, so close as to be right here:

“Thin places are potent doorways within our sacred world, which includes the natural world (and aspects of our human world) and also domains that permeate and lie beneath our world. It is where the ordinary and non-ordinary come to rest in each other’s arms. These places might be in-between places or particular in-between times, such as twilight. Celtic thin places are crossroads where the world of spirits and the world of the embodied mingle. It is where the realms of human and faery touch. It is where living descendants and the ancestors commune. It is where the unseen and the seen share one ground.”

In your life, have you encountered such places? A good way to consider that question may be to take yourself back in memory to childhood. Were there certain environments where, before the mainstream, logic-locked narratives of our culture took over, you felt especially alive in the presence of land that was alive, too, and in its own way, speaking to you? Before well-meaning adults convinced you that trees and streams don’t have messages, and the spectral connections you feel—those otherworldly communications—aren’t real, but purely imaginative. What, if any, thin places have you known by your own sensing? Subjectively, beyond proof. Confidently, beyond questions of how, or concerns for the good opinions of others.

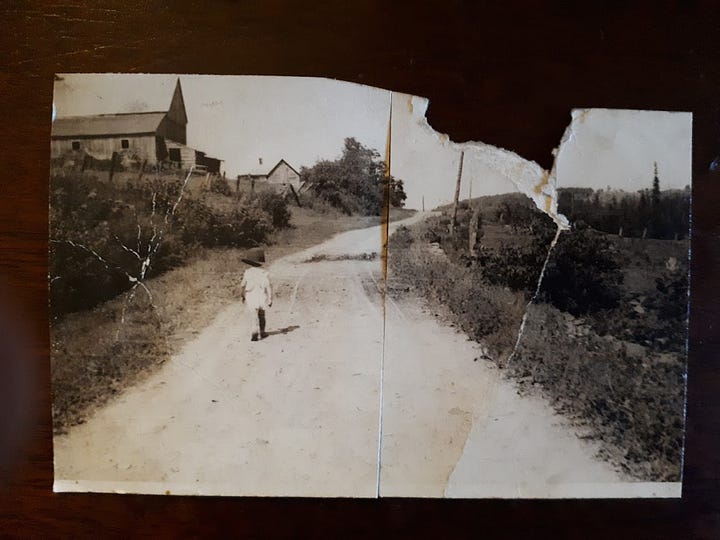

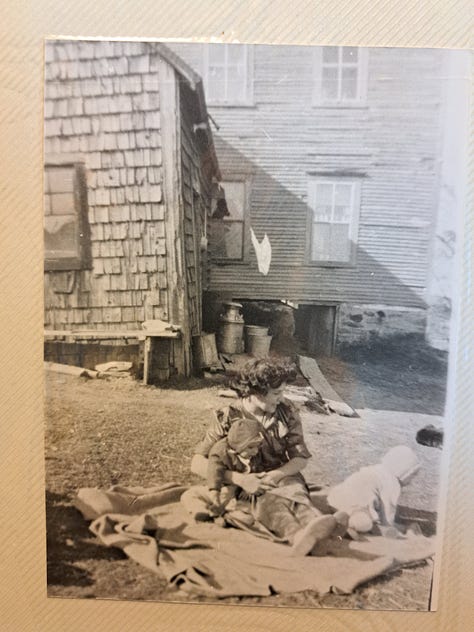

After stopping by a burial ground where we’d been once before, a fenced patch of earth bearing the remains of generations on both sides of my gramma’s people—her grandparents and their parents, some of the many aunts and uncles and neighbours who’d help to raise her and her brother in the absence of their mother, and Gram’s parents and brother, too—we took a drive down an unpaved road toward the house I’d been pondering since 2021. Our compass: my stepmother’s scant description based on a trip she’d taken with Dad in the early ‘90s, a small painting, a half-intact 1930s photograph, and goosebumps.

In the picture, my pre-school-aged uncle Derek marches up the road to his grampa’s farm. Gram made sure they visited her father each summer—in those days, travelling over 700 miles by train from Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario—adventures even my own father, the baby of the family, got to share in before Ernie sold the land and its structures to a French-speaking neighbour in ’45.

In the years when my ancestors lived there, French and English families (and of the latter, mostly Scots-Irish) farmed alongside one another in that region of Québec. They turned out for the dances and shared in one another’s lives beyond the confines of language. In 1960, on the evening before Jessie’s burial, eight years after Ernie’s death, once her body had been returned from Montréal to the village of South Durham, an elderly French Catholic neighbour—one of the few locals who remembered her—insisted on sitting with her, saying prayers, and keeping a vigil by candlelight throughout that long December night.

The House of Memory

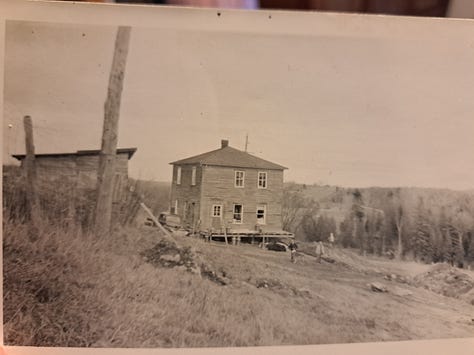

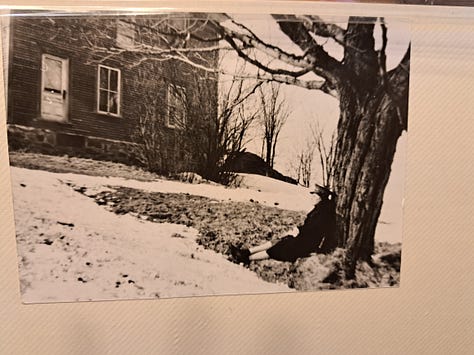

It didn’t look very old. That’s what the logical part of me kept saying about the farmhouse I’d photographed back in 2021. Now, here we were again, at the same bend in the road and the same home with its grey vinyl siding that seemed so… contemporary. It was the place I’d asked my husband to drive us to immediately on the previous night, after arriving at our hotel, thirty minutes from this quiet (and not so quiet) stretch that kept calling to me. On the evening before, the farmhouse had seemed deserted, its windows dark. We’d parked under the almost-full moon, gazing out at the blue-cast fields and at the shadowy hill beyond. The tingling along my neck and shoulders, talking to me. And something else. Someone? Perhaps it was the same presence that had caused me to want to pull over four years earlier and take pictures of the fields here, including one of Hugh and me, standing by the road’s edge where the land sloped down—a clue in the old photo.

Now, here we were again in daylight. Outside, near the barn, a man was seated on the back of his truck. We pulled into the driveway and parked, doing our best in French to explain the reason for our visit. Out came the heavy canvas tote—my heart bouncing, my French awful but clear enough to get his attention. And finally, a grin. Then an invitation inside.

The ancient Celts had a belief in something they called “Oran Mór,” the Great Song of the universe. In The Mist-Filled Path, MacEowen writes that “the trees sing, the stones sing, the waters sing, the wind of the clouds sing, and the ancestors sing. Life is music. All things have their rhythm. The world is sound.” He muses:

“Oran Mór can also be a deep spring that fills the sacred well of the human soul. This quenching power flows, moving majestically, beneath and within the world. Occasionally, and not often enough in my estimation, Oran Mór emerges, like small pools in a desert. Then, ‘that which can be known but not spoken of’ is felt as an undeniable presence, in places of power in the landscape and places of memory in the soulscape in the life of the individual and community…”

Was that the music my heart was dancing to as I crossed the farmhouse threshold?

During the First World War, in the aftermath of his wife’s diagnosis and the assured guidance of her doctors, convincing Ernie it was best to leave her be, he had taken his children to the States to live first with a sister in Irvington, New Jersey, and then with another sister in Boston, finding jobs in construction. Maybe he’d done it simply for a change. Maybe to escape. Who knows? In her journal, Gram writes only briefly of going to school there. And of being glad they went home. Because something brought my great-grandfather back. Not to the fine farmhouse he and his wife and their little ones had shared. That was gone. But to the land. To both sides of his children’s family. To acreage his parents and siblings had farmed for decades. And a chance to start over.

Unlike my great-grandfather’s violin, it turns out that beneath the surface details of a 1980s renovation, the house he built remains intact.

Over the years, for the two families that have lived there since 1918, it’s been a place that signalled new beginnings. While we were visiting the current owners, suddenly poring over two families’ old photographs, looking at yellowed deeds of sale, and moving through rooms and into stories in French and English—Réjean, the grandson of the man to whom my great-grandfather sold the farm, pointed to an area of the living room floor and laughed: “Je suis né là!”

I was born here.

Sometimes, especially in this stretch from Hallowe’en season to the Solstice, looking back, we can feel a cave of longing inside us. Wishing we could be with loved ones who’ve crossed over. Wishing that some things had been different. That we could walk amongst our ancestors, and laugh and dance with them, too.

But who’s to say we’re not doing that now? On both occasions when I’ve travelled to the lands where my gramma’s people lived for a brief while, numinous experiences have brought me into resonance with an understanding beyond words. In such moments, the cave inside me becomes a hollowed instrument that sings. Across time, while our individual songs are unique, I like to think they’re part of a greater weave of sound. The whole universe is music. We can’t not be connected.

Such a beautiful, poignant ode to kinship, listening, and the deeply woven fabric of our connection. I recently visited the Llangynidr valley in Wales where my father's people are from. A distant cousin still lives in the updated 1700's farmhouse and is the village and our family genealogist. That valley and many other places in Wales were "thin" and I would find myself spontaneously weeping--feeling a transcendent sense of belonging. Thank you for this beautiful story and the reference to The Mist-Filled Path...I love the photos--especially the fiddle.

Robin, your ancestral longing and offering is breath-taking! What a deeply tender weaving of memory, land and song. Your words carry the ache of what was lost and the quiet miracle of what still sings beneath the surface. Thank you so much for letting us walk with you through these thin places, where the unseen and the seen share one ground. So perfectly placed this week in the run up to Samhain. And the photos, I have to mention the photos because together with your words they feel like a 'true' marriage of word and image. Bravo! 💖🙏🕯️