When was the last time you felt a sense of wonder?

I believe we yearn for it—that glimmer of the vast and mysterious—because somehow, whether wonder guides us inward or points to something bigger than ourselves, it gives us hope.

That’s why I write.

To experience awe in a story unfolding. To feel a sense of the uncanny. Strong emotions. To call upon unseen forces, an inner knowing—tingles.

Connection.

Like me, my readers are heart-centred, independent thinkers inspired by unusual journeys of healing and growth. We root for characters who face tough challenges that we can empathize with and feel. Characters who defy the odds in following their own inner compass. We love journeys through time. Here, in our own time, it can be easy to feel like an outsider, because even though we’re rational and educated in the ways of the world, we also see beyond the limits of conventional pathways. We honour the power of dreams. And words.

As a poet, I delight in the wonder of language.

As an historical fiction author, I weave elements of the metaphysical and supernormal into my complex characters’ stories. My books are about family secrets, ghosts, difficult journeys, exhilarating journeys, and the importance of using our gifts. They’re love stories.

I’m thrilled to share that my new novel, River of Dreams, will soon be published. Set a century ago, it illuminates the power of one woman’s dreams and intuitions, exploring her drive to learn the truth about her real mother and bring healing to women who would otherwise stay shut away and silenced.

I believe that, to one degree or another, we’re all intuitive. And that our dreams and intuitions are creative catalysts and guides. What happens when we say yes to our own inner knowing and dare to create at a new level? Wonders happen.

In addition to being a writer, I am also a teacher and life coach devoted to helping you clarify your dreams and bring your visions into form.

Official Bio

Robin Blackburn McBride is a Canadian novelist, poet, and coach. Her first full-length work of fiction, The Shining Fragments (Guernica, 2018), is an Editors’ Choice selection in Historical Novels Review. Her self-help book, Birdlight: Freeing Your Authentic Creativity, became an Amazon Best Seller in 2016 and has since been released on Audible. Robin’s poems have been published in anthologies and periodicals. In 2002, Guernica published a volume of her poetry, In Green.

Robin’s forthcoming novel, River of Dreams, is a stand-alone sequel to The Shining Fragments. Excerpts from the manuscript have appeared as short stories in five North American literary magazines.

For many years Robin worked as an English and language arts teacher in Toronto, including two decades at Branksome Hall. Before that, she worked as an actress. Robin holds degrees in English, drama, and education from the University of Toronto, where she was a faculty scholar with high distinction who received a Samuel J. Stubbs award for academic achievement and two W. J. McAndrew awards for drama (performance). As a devoted learner, when she is not writing, coaching, and delivering her own workshops, Robin continues to hone her craft through mentorship and professional trainings.

Robin has a lifelong passion for the arts, local history, and metaphysical studies. She’s a lover of long walks in the woods, and an active supporter of social justice and environmental protection—in particular, the preservation of old-growth forests.

In addition to writing, Robin serves as a professional life coach specializing in transformation and creative fulfillment.

Robin lives with her husband, Hugh, and their black cat, Poe, in Gatineau, Quebec.

A Brief Journey Through Time

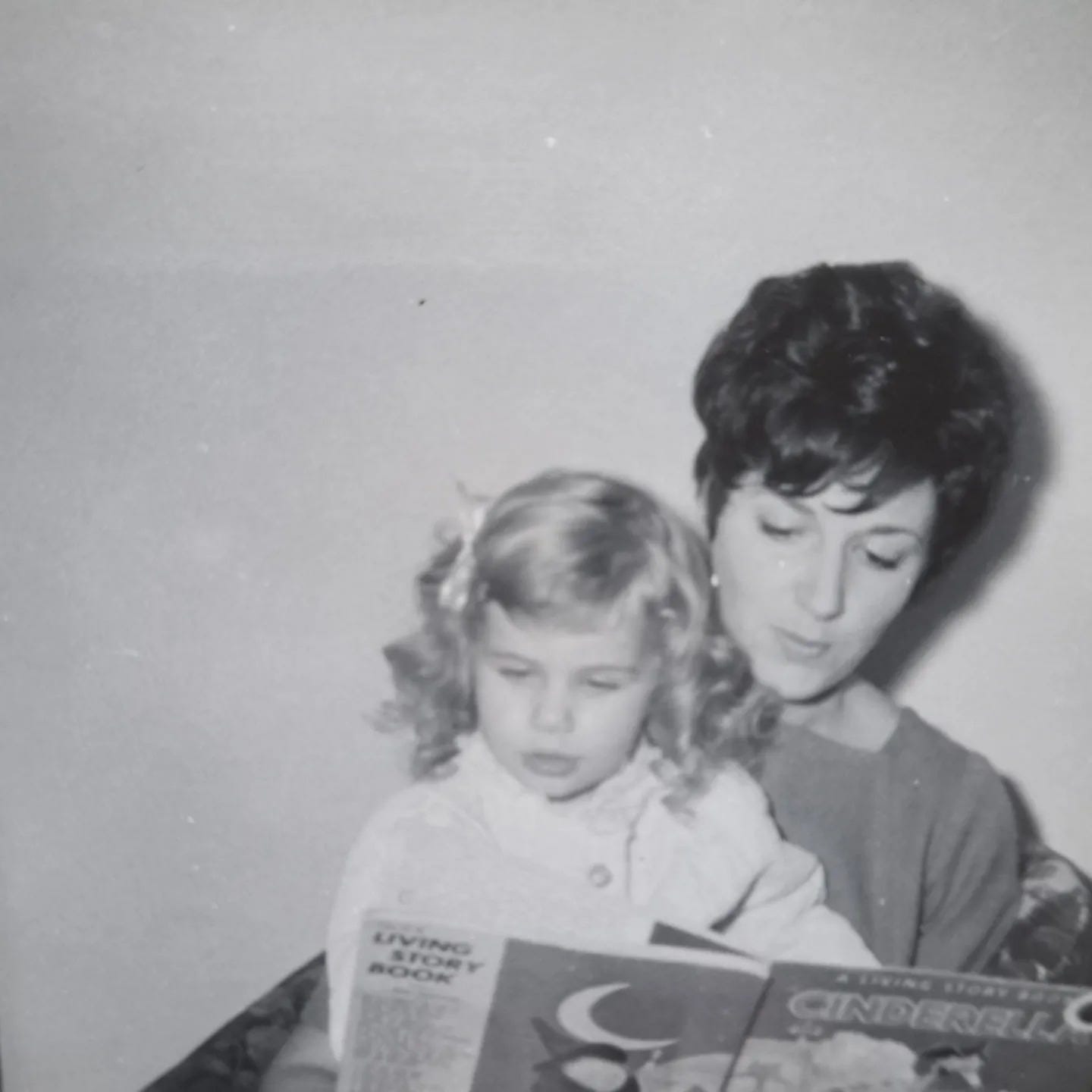

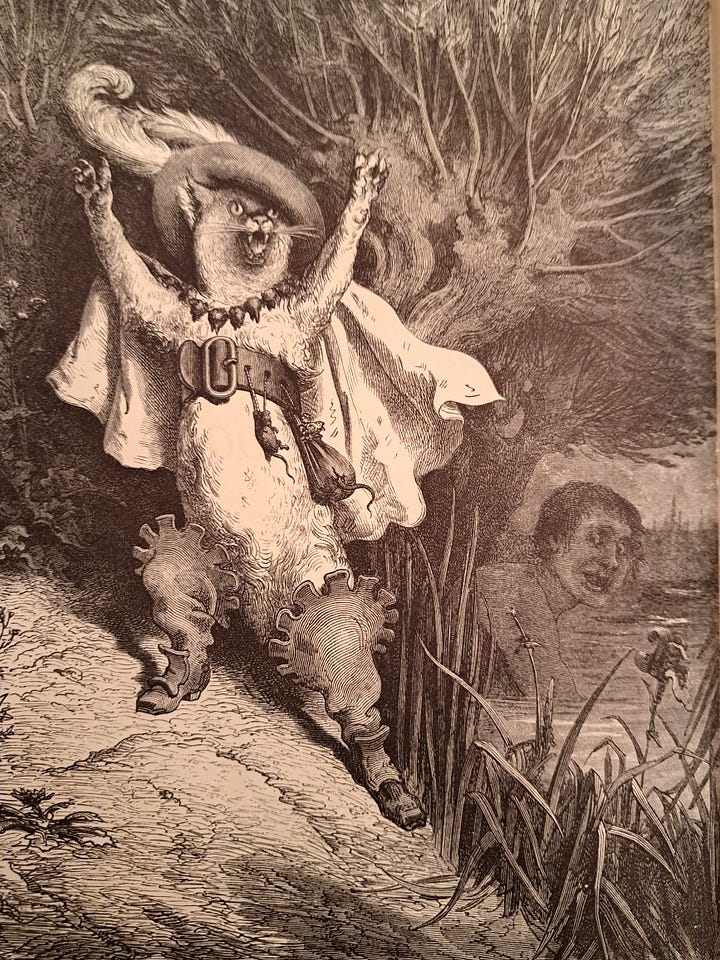

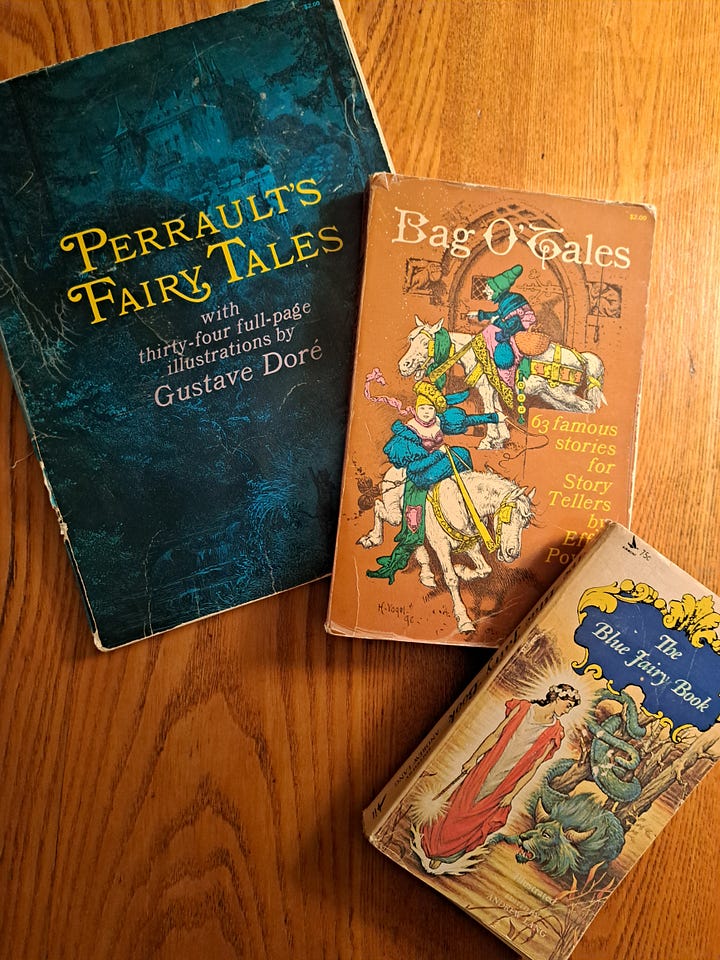

My formal studies of literature and private trainings with writing teachers may never have happened if my mother hadn’t read me fairy tales that made my eyes widen and the hairs on my arms bristle.

Growing up in a family of teachers, lawyers, political activists, and artists—a family of strong opinions, dramas, big tempers, bursts of laughter, loud parties, and long silences—I learned quickly how to retreat and find enchantment.

My paternal grandmother was a keeper of family stories. Sitting with her for hours, alone or with my cousin, I’d beg Gramma to talk about her departed elders and life on the farm where she’d grown up in the Eastern Townships of Quebec. As a city kid, I did my best to imagine her early world. Gramma took me to the old country, too, as she’d heard tell of it from her people, who’d heard tell of it from theirs. And I’d marvel at the idea that my ancestors had come from across the sea.

Would I have written The Shining Fragments if I hadn’t been enthralled by my grandmother’s recollections? I’m not sure.

Some of my family’s stories were haunting. Tales of people who were lost. And I came to wonder about ghosts—not in the way I had when I’d feared them as a small child prone to nightmares, but in a different way. A new way.

In Toronto, where I grew up, I learned to feel into the past at certain street corners, sensing the layers of time. My little Etobicoke house could disappear and become a farmer’s field. Then a meadow by a river valley. Like so many of us, for me, nature has always brought feelings of awe and quiet amazement.

So has reading.

The first novel I read independently, in third grade, was E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. Oh, my God—it blew my mind that a book could do that! Take you right to the edge of life and death, fill you with love for characters who’d gotten into your heart, break you open, and leave you sobbing. What an amazing thing. A private thing. A book could change your life.

Novels and their authors became an essential part of my reality. As a child, I read stories set in the past as if I’d just come from there and couldn’t quite get used to this 1970s suburban reality I was in. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series and L.M. Montgomery’s Anne books became early portals to other worlds. As well, works by contemporary, alternative writers, such as Zilpha Keatley Snyder, fed my hunger for awe and possibility through depictions of what we’d now call the supernormal. Even then, I felt a deep pull to esoteric subjects.

These days, I’d love to write a story set in 1970s suburbia.

Early Pages

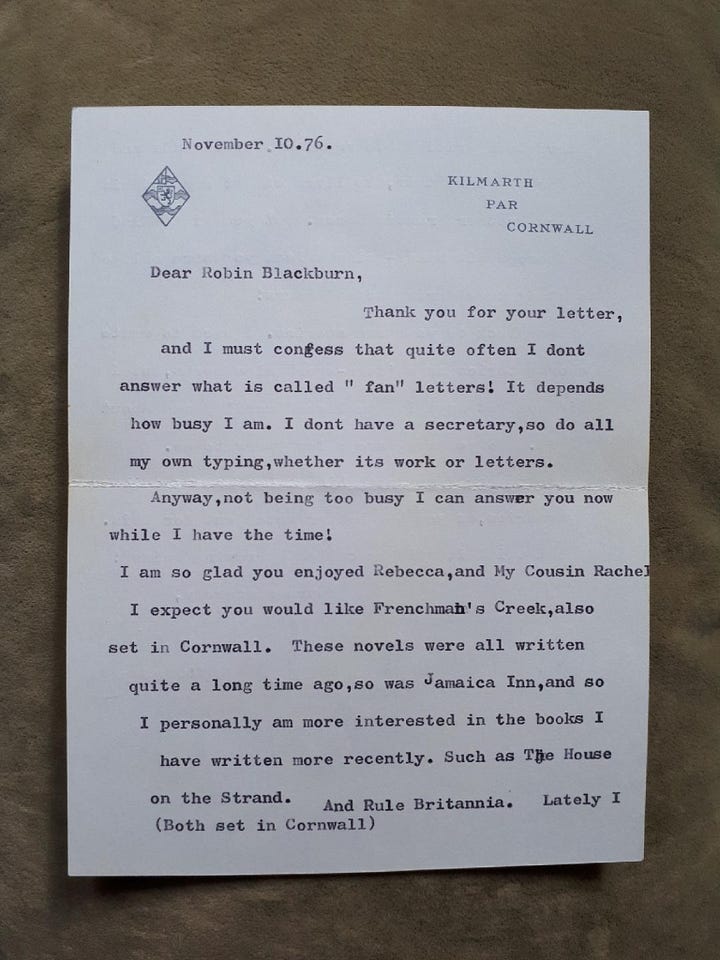

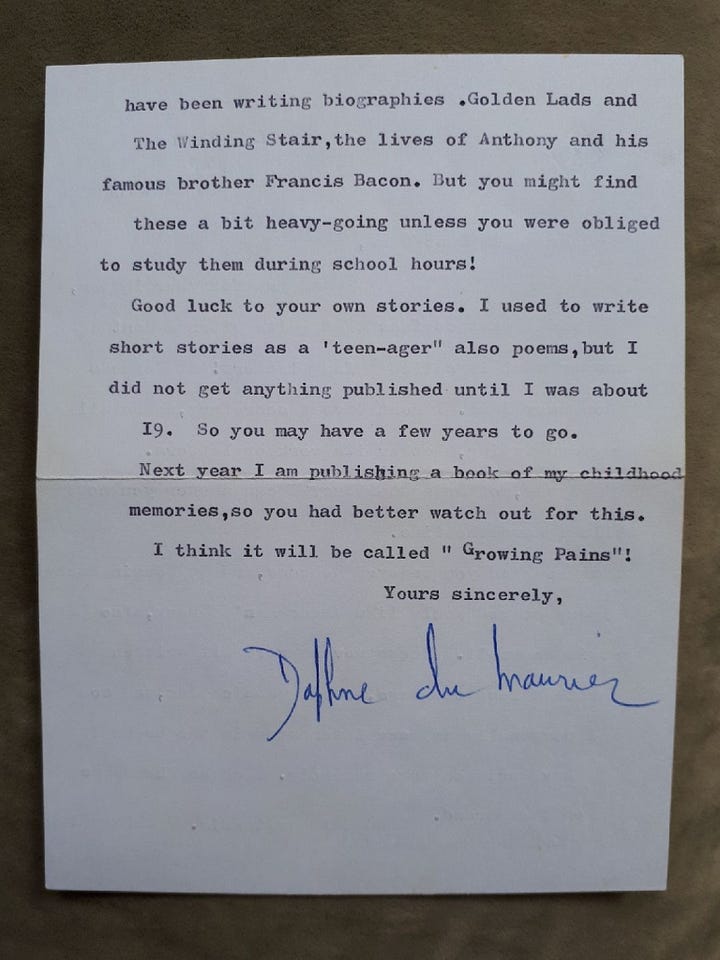

In elementary school, my little pine desk became a kind of church, as did (in the summers) a little brook in the woods near my maternal grandfather’s cottage at Lake Huron. Summers freed me to become interested in adult literature, and between fifth and sixth grades, I discovered Daphne du Maurier, reading a 1938 Doubleday edition of Rebecca, tucked into an alcove on a sea-blue couch. At the time, almost eleven, I marvelled at how plot twists and ghostly atmospheres could make me feel at home in myself. Watching old movies on a twelve-inch black-and-white television at the cottage, I fell in love with things gothic. And after reading more of du Maurier’s early novels, I wrote her a fan letter. She wrote me back!

All of those things led to drafting my own poems and twisty tales of suspense in middle school, where I had an exceptional teacher, John Armstrong, who typed them for me. During our three years together, Mr. Armstrong collected my writing, fastening it into a book that we presented to the school library when I graduated from eighth grade.

Decades later, I reclaimed that faded Duo-Tang-bound volume. Not just out of sentiment or for fun. I needed to believe in myself again.

By the time I was a thirty-something single mother living in a small Toronto apartment, it had been ages since I’d painted my little pine desk black to fit with someone else’s aesthetic. Ultimately, I’d given the desk away—that magic place where I’d written my first poems and stories. How many times, in the years that followed, had I wished I had it back?

But what I really wanted was to be writing.

Stages

In university, I studied drama, including the plays of Henrik Ibsen who was a feminist ahead of his time. It would take me years to fully appreciate his work. As a twenty-year-old undergraduate, I was blind to the notion that women still didn’t have fair treatment in our culture. And I had yet to fully grasp how necessary it was to be—and remain—a feminist. To my last breath, I’m someone who champions women daring to claim and develop our gifts. To step into our light, regardless of age—making contributions to a world crying out for greater balance. For greater honouring of feminine ways and wisdom.

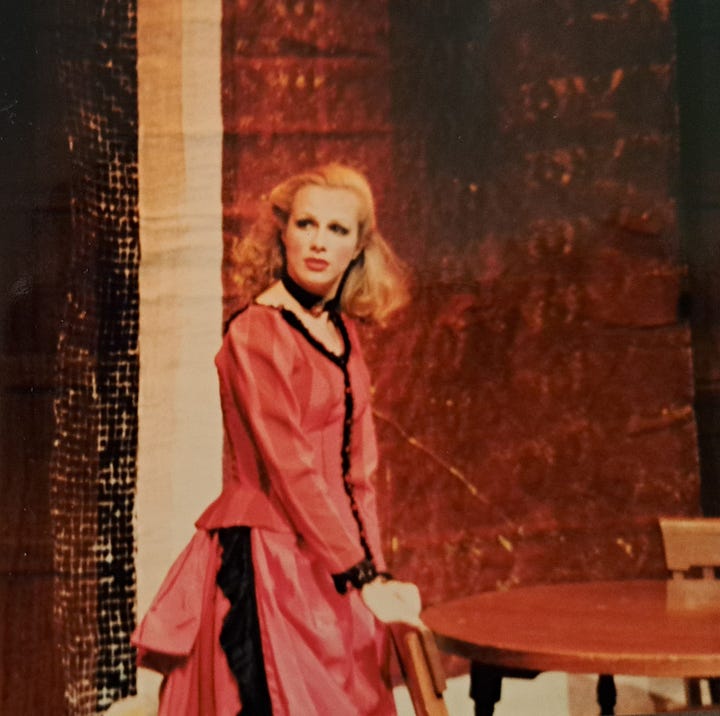

Working in theatre brought me to wonder. I inhabited roles and worlds that took me into the past in a way I’d never experienced before. I did my drama degree backwards, starting with Harold Pinter and wending my way to the ancient Greeks. But every phase was a portal to somewhere sacred, somewhere so alive that when a play closed, I felt a little death, carrying the memories like those of lost loved ones.

My dream was to continue working as an actress, and for a few years, I did. But out of school, so often it became an exercise of waiting for auditions and for others to make decisions. Of fielding rejections (in those days my skin was tender). Of making do with shallow roles—the ingenue, the soap commercial girl—if I was lucky. I had passion and stage presence, but in competitive circles, surrounded by big personalities, I found myself rapidly losing confidence.

Have you ever been in that place? If you have, then you know how a lack of confidence only becomes a magnet for further disappointment.

My early twenties were half ecstatic and half soul crushing. I felt like part of me had died. And while I wanted to have more control over my creative life—to make a career in the arts—I wasn’t sure how to find my way back to the part of myself that knew how to dream things up and bring them into form.

Finding a Way

In my first marriage, I set up offices in apartment storage closets. Even if it was hard to breathe inside a closet, I didn’t care—it was sacred space, and I’d spend hours scrawling poem fragments. The beginnings of stories. How I wished I could channel my eleven-year-old self and finish things. So much of my life felt like a work in progress with no guarantee of anything.

After my daughter was born, I went back to school, specializing in English, and later training to be a teacher—a straightforward, stable path. Even if I felt part of me was missing.

Yet teaching school for many years helped me to find wonder in the children and teenagers around me. It was an exchange of gifts. Some of the best times were off-road adventures—directing children’s theatre, running creative writing clubs and projects, creating spaces where young people could be free to express themselves and be zany, serious, inquisitive, challenging—experiences that didn’t culminate in marks.

In my novels, the main characters begin as children.

What is it about the journey from childhood to adulthood that I feel compelled to look at again and again? What clues does that process hold to what it means to be a human being?

Code

Often, I’ve witnessed in others the same deep desire I’ve felt many times—to call a child part of the self back home. To become a safe place, to be whole. To find the curious, uninhibited, playful, and highly creative part of us that knew things and had things to say. One that still has things to say.

In his book, The Soul’s Code, Jungian analyst James Hillman suggests that each one of us has an inner “code” or calling. A voice of the soul—the still small voice that knows who we are, why we’re here, and how we’re meant to live. With all parts working together.

That’s the voice I love helping people listen to and honour. But I wouldn’t have been able to do that very well if I hadn’t listened to, and honoured, the voice of my own soul.

When I left full-time teaching to step into life as a writer at mid-career, it was scary. Yet somehow, I knew to trust myself and find community. Then I found help through transformational life coaching. Being on the receiving end of coaching was so inspiring and emboldening that I decided, in addition to working as a writer, I’d train and serve as a life coach, helping others to make expansive, soul-honouring moves—to reach new levels of clarity, focus, resilience, and amazement.

My book Birdlight: Freeing Your Authentic Creativity tells the story of that pivotal phase in my life. I wrote it as a guide to helping you learn how to live from a vision, take action for what you love, and overcome the inevitable obstacles that aren’t barriers, but qualifiers for the adventure.

My Why

I believe art is a work of soul. And that good stories and poems are guideposts for connecting with our deepest and most essential self. That’s why I love writing and feel a sense of awe and humility in working to get the pieces that come through me as far as I can.

It’s also why I love helping you to get clear on any limiting stories you may have come to believe about yourself. And to find new stories. Better ones.